The retirement time bomb: Pensions and insurance for emerging customers

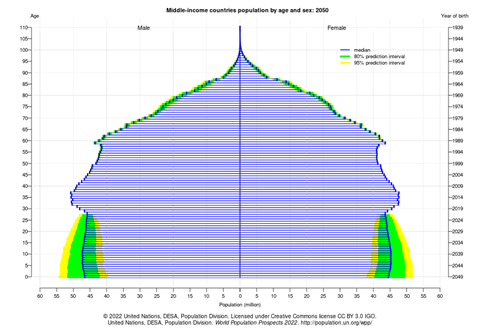

As the baby boom generation of the 1950s and 1960s reaches retirement age, it continues to shape the global economic landscape. And, as advancements in medicine and science have increased over the decades, people are living longer than ever. At the global level, those born in 2019 can already expect to live 6.5 years longer than those born in 2000, and when we look at regions, such as Africa and Southeast Asia, life expectancy increases further to 11.8 and 8 years respectively. By 2050, there will be 2.4bn over-65's worldwide. This has, however, been coupled with a declining birth rate which is changing the age structure of many countries, including those in the developing world.

Source: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division

All this is paving the way for a global pension crisis. The current model of traditional state pension systems, which rely on younger generations funding the retirement of older generations through social security payments linked to work, is not sustainable. The amount of money required to support the ageing population far outstrips the amount being paid in. OECD countries are already having to take measures to tackle this – such as raising the pension age – however the problem is more pronounced in developing countries. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa over 80% of the working population aren’t covered by any pension arrangement yet, by 2050, it will be home to the highest number of retired or aged people globally.

Informal workers face precarity in old age

This is largely due to the high proportion of people working in the informal sector. In these cases, there are few mechanisms that compel informal workers to contribute regularly to a pension fund. For those who do have enough money to save for old age throughout their working lives, many do not have the financial education to know why they should, or how to access long-term savings and pension programmes (which are usually designed for formal employment). And many informal workers simply do not have enough money to save, or the consistency of income to be able to pay into a formal scheme.

Even within the formal employment sector, enforcing payments into the state pension programmes can prove challenging, as is the case in Nigeria. Here, the Pension Reform Act requires monthly payments to be made into a pension plan through a defined contribution scheme where employers contribute 10% of the salary and employees contribute 8%. The money is then released on retirement. Despite this, only 15-17% of the labour force had pension accounts as of Q2 2022.

There are several reasons that could explain this lack of future planning in Nigeria. Firstly, there is little education around how to access these plans which means many employees who want to save, aren’t always aware that there are provisions for their employers to help them do this. Another reason is that many small businesses often don’t realise that they need to provide pension plans, even though the law mandates it for companies with more than 15 employees. And some businesses, despite knowing the law, choose not to accumulate the extra cost of putting a plan in place, even with the risk of a 2% penalty. The regulator – PenCom – has recently tried to crack down on these companies, however there are many who have still yet to remit the funds.

Other developing countries are taking steps to ensure the elderly population are supported financially. For example, in 2017, the Kenyan government introduced a tax-financed social pension called Inua Jamii 70+. This is a cash-transfer programme – one of the largest in the region – that offers KSH 2000 (roughly equivalent to USD 20) per month to those aged over 70. The aim is to alleviate poverty and improve the welfare of older people in the country. As of 2020, the programme had reached 833,000 households with older people.

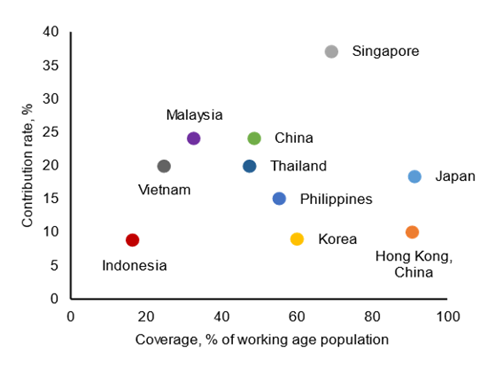

In Indonesia the pension system consists of mandatory and voluntary earnings-related schemes. There are several mandatory schemes for formal workers as well as voluntary ones offered by employers and financial institutions that formal workers and the self-employed can access. Despite this, the mandatory pension system is relatively small compared to other countries in the region with only 16.5% of the working-population actively contributing, compared with around 20% in Vietnam, 25% in Malaysia and 35% in Singapore. Additionally, the value of contributions is very low, with total assets amounting to around 3.3% of Indonesia’s GDP, compared with Malaysia’s Employment Provident Fund (EPF) at 65.5% of GDP and Singapore’s Central Provident Fund (CPF) at about 85.3% of GDP in 2022.

Source: ASEAN Macroeconomic Research Office

As a result, reforms are needed with solutions such as raising the retirement age from 55 to 65 (which the government has been doing incrementally since 2014), preventing the withdrawal of the pension until retirement age and increasing the mandatory contribution rate.

The role of the private sector in bridging the gap

However, just as OECD countries have had to introduce additional pillars to support the state pension programmes, it is inevitable that developing countries will also need to look to the private sector to help mitigate widespread poverty among the aged.

One way of tackling the issue in countries where informal work is common is to introduce micro pensions. This type of scheme is a voluntary, defined contribution individual account plan for the informal sector or low-income earners, which allows voluntary savings to be built over a long period of time. Key to this type of pension is the recognition that, while poor people and informal labourers may be able to save some money throughout their lives – and many of them do save - they cannot do this in a consistent way. Field studies have indicated that the poor prefer to make small and frequent contributions to a savings fund. And, because of the precarity of their livelihoods, sometimes they need to withdraw money when emergency situations arise. So, these long-term saving schemes need to have an element of liquidity balanced by provisions that discourage taking out more money than is necessary before retirement.

By encouraging those who are excluded from traditional pension schemes to save just a small amount regularly through a micro pension, not only will they gain some element of financial security for old age, but it removes the financial burden on governments to support the whole population through a universal pension. By 2050, there will be 600m over-65s living under the poverty line and 1.2bn working in the informal sector. If just 10% could save USD 1 a day, they could collectively build assets of USD 850bn within a decade. Looking at Nigeria specifically, which has 59.6m informal workers, if each contributed N100 weekly through a pension fund that invested at a real rate of returns of 4.5% per annum, after a year the country’s micro-pension industry would be worth approximately N61.1bn (roughly equivalent to USD 80m). This is an attractive prospect for governments and pension providers.

A holistic approach promises best chance of success

However, to have the best chance of success, those developing micro pension products should consider bundling them with other services and activities that benefit the users. For example, with components such as liquid savings for when large expenses (e.g. children’s education) arise; insurance to provide peace of mind in case of emergencies such as illness or destruction of livelihood; and digital payment platforms to make saving and withdrawing money easy. By providing a holistic financial support structure, people will be incentivised to save for their future.

And some organisations are already offering these types of products. For example, pinBox, a social pension technology provider has helped to develop inclusive digital micro-pension schemes for non-salaried workers in developing countries. In 2019, they launched the Ejo Heza programme in Rwanda which reached 2.4m voluntary subscribers (50% women) within three years and resulted in RwF 50bn (roughly USD 41m) in new long-term savings mobilised. They have also launched their micro pension model in Kenya and India.

As populations continue to age, it’s crucial that governments consider how to ensure financial security for their older citizens. With the current pension model unsustainable and not fit for purpose in most developing economies (given the large informal labour force) it’s time to consider alternatives from the private sector that are designed specifically to meet the needs of this large – and growing – sector of the population. Micro pensions, particularly when incorporated with other inclusive financial tools such as insurance and short-term savings plans, will not only help provide security in old age, but also financial resilience throughout people’s working lives. In addition, new inclusive pensions that account for the challenges poor populations face in developing countries – such as the impacts of climate change – can also be designed in a way that mitigates these sorts of risks. This could help them to leapfrog the challenges traditional pension schemes are currently facing around incorporating climate change into their investment models. With such a large population excluded from the traditional pension system, the use of micro pensions would likely be a win for all involved: governments, the private sector, and of course the workers themselves.